At the Villars Institute Summit 2024, Lord Malloch-Brown was invited to deliver the 3rd Villars Institute Distinguished Lecture.

He shared invaluable insights, drawing from his vast experience, on the challenges and opportunities shaping the geopolitical and multilateral context, and the pivotal role of communities, coalitions and connections on the critical pathway to progress and prosperity within our planetary boundaries.

Below is a transcript of his insightful lecture.

Remarks as prepared.

Thank you for that introduction. And thank you for the honor of this invitation to give the 3rd Villars Institute Distinguished Lecture.

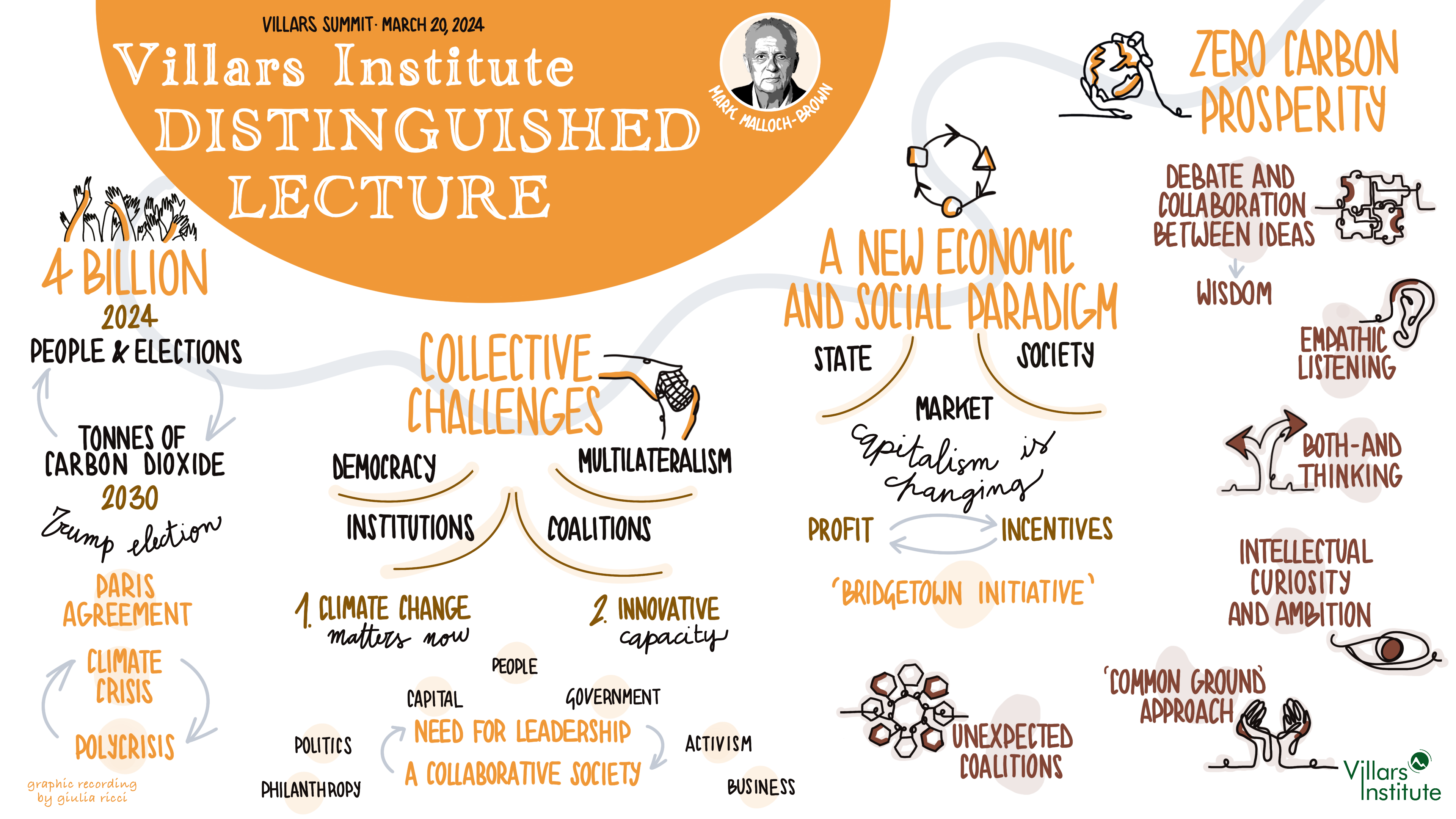

Let me start with a number: 4 billion.

A number relevant this year in which states with a combined population around that figure are holding elections of one form or another—the largest of any year in history to date.

But four billion is also the number of additional tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent that will be emitted by 2030 in the event of a Donald Trump victory at the U.S. presidential election in November. That, at least, is one authoritative estimate based on the GOP platform and the former president’s specific commitments.

That estimate is apparently without Trump’s promise to “drill, baby, drill”—but it would nonetheless...

- correspond roughly to the annual CO2 output of the EU and Japan combined,

- almost double the percentage-point gap between U.S. emissions and its targets under the Paris Agreements,

- and negate twice over the total global emissions savings from wind, solar, and other clean technologies over the past five years.

It is a sobering reminder of how much is at stake in November. And the perverse outcomes democracy can deliver for the climate. It is not always a friend.

Around the world we are seeing “greenlash” dynamics as electorates strained by the increased cost of living turn against climate policies perceived—accurately or often inaccurately—to be at fault.

Just look at the wave of agricultural protests forming the backdrop to the European Parliament elections in June.

In some cases, we are seeing authoritarians converting this discontent into fodder for culture-war politics. Witness how Marine Le Pen in France and the AfD in Germany have hugged the demonstrating farmers close.

And most of all we are seeing the link between the climate crisis and the broader crises of our polycrisis age simply go overlooked.

One of the most remarkable aspects of India’s election campaign as it gathers pace is just how relatively marginal climate issues are within it despite the catastrophic floods, droughts, and heatwaves the country has experienced in recent years.

It all begs some difficult questions:

- Is democracy fast and far-sighted enough to rise to the challenge of attaining net-zero in time?

- And can a system that is by its very nature shaped by the swirling complexities and inconsistencies of public sentiment drive through the transformation of industrial modernity within the short time available?

On a bad day it can feel like we are asking a system that operates in zigs and zags to find the most direct line from point A to point B: point A being our present annual carbon dioxide emissions of some 40 billion tons and as many as 2,000 species extinctions per year and point B being a lastingly carbon-zero and nature-positive world.

And that applies to multilateralism, too—in many respects democracy’s sibling.

The multilateral institutions might be compared to a camel train crossing an inhospitable desert without enough water.

All-too-often the caravan’s pace seems to be set not by the vigorous camels at the front, striving towards the horizon, but by the mangiest, slowest nag at the very back.

COP28’s language about the need to “transition away” from fossil fuels was greeted as a radical breakthrough. And indeed it was a positive step, but one that lagged the science and the urgency of the matter by decades. I suspect everybody in this room takes it for granted that we have overshot, or will overshoot, Paris.

The mismatch between the change needed and the systems we have for delivering it can be dispiriting.

But before we blame democracy it is worth reminding ourselves that authoritarian governments do not necessarily have a better track record. Russia and its fossil fuel extracting cousins bury their heads in the Kremlin sands and live off that Trump maxim of “drill, baby, drill."

China has for mercantilist reasons built a dominating lead in renewables technologies but remains in the domestic grip of “Comrade Coal.” In 2023, it approved 114 gigawatts of new coal power capacity in 2023, up 10 percent from 2022.

Increasingly I have come to believe the challenge is less about the form of government and rather about, first, winning the argument that climate change matters now; and second, about the capacity of different societies to unleash the forces of innovation, capital, people, and government.

On all those scores democracy enjoys a strong starting advantage. It is better placed to marshal the forces of pluralism, contestation, and most of all partnership needed.

For that is the essence of the crises of climate and nature before us: to reconcile what can often seem to be opposed imperatives:

- to seek to mitigate climate change but also adapt civilization and nature to it;

- to set a long-term course but also be nimble and adaptive in pursuing it;

- to respond to public sentiment but also lead and shape it;

- and to deliver all that change at scale without succumbing to the logic of the lowest common denominator.

So yes, we need breakthroughs, transformations, revolutionary shifts. But if they come, they will be the function not of purisms and absolutes but of pluralisms, hybrids, and the mantra “don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.”

They will comprise the lowering of guards and the abandonment of old assumptions in the service of new and often unexpected coalitions at all levels—between states, and between and within peoples.

Because as it is frequently observed of climate change: it is not a one-nation problem but an all-nation one.

Take relations between states.

Nearby Geneva is a palimpsest of multilateralism. It is thus a reminder of how the international system has been plagued by the logic of “nothing is agreed until everything is agreed” from its very beginning—from the time of the League of Nations to today’s deadlocked United Nations Security Council.

But that history also speaks of how that one-speed logic can be circumvented by dynamic leadership and coalitions of the willing.

My own career in the multilateral institutions began back in the 1970s, a time with obvious resonances today.

The world seemed to be beset by crises, as potentially cataclysmic superpower tensions vied with regional wars to keep us multilateralists awake at night.

The prevailing economic order seemed to be crumbling as the post-war New Deal or Welfare State era gave way to what we would today call the neoliberal one.

The optimism of a brief post-1945 multilateralist golden age some three decades before had faded—as the so-called “last of the Mohicans” present at the UN’s post-war temporary digs on Lake Success were only too keen to tell us freshmen officials.

Many back then feared that the UN would go the way of the League before it. But the post-war multilateral system turned out to be a hardier organism, one that could grow into new spaces. The UN’s political vocation was blocked, so it became a global force for humanitarian action.

I experienced this close up running refugee camps on the Thai-Cambodian border in the late 1970s that housed hundreds of thousands of Khmer, and still recall the astonishment of Kurt Waldheim, then Secretary-General, when he visited and discovered that this had all been established without him even realizing. A new face of the UN far from the bureaucratic and political quagmires in New York and out of sight of the deadlocked Security Council.

I suspect that the system will prove possible of such “multilateralism among rivals” today. It will grow into the spaces available.

Geopolitically, the world of the mid-21st century looks set to be divided and contested. A new Cold War looms.

But it will also be a time of obvious and substantial shared interests where the climate and nature crises, and the economic architecture needed to address them, are concerned.

It will necessitate odd bedfellows; diplomatic and political hybrids whereby geopolitical rivals can work together on the state of the planet even as they struggle for its political and military control.

Will the system make that possible?

It will need the right leadership. That is why, under my presidency, the Open Society Foundations has been a stalwart supporter of the Bridgetown Initiative led by the astonishing Mia Mottley who from the little island rock of Barbados has shown more superpower leadership than Presidents Biden or Xi. And the V20 group of finance ministers from now 58 climate-vulnerable states.

It is also why the choice of the next UN Secretary General will be crucial. Working closely with Kofi Annan, I saw first-hand the difference that dynamism and vision in that role can make. When the world disagrees it is either a reason to do nothing, as his successors have too often concluded, or an opportunity to seek out points of overlap and paths through as Kofi sought to do.

But it will also need the right institutions and even institutional innovations. The idea of an Economic Security Council has bumped around the multilateral system for decades. Now would be a good time to update it—as an economic and climate body—and finally make it reality. Multilateralism among rivals made real! In what might be called a Sustainability Security Council built among the fast camels not held up by those at back of the pack.

Start with democracies, a minilateralism if you like, but don’t use the form of government as a barrier to entry. Break with North-first clubs like the OECD.

Let the Indias, Brazils, and South Africas (the three sequential G20 hosts) kick this off with humble support from western democracies and like-minded fellow G20 members. A group that is responsible for 85 percent of GDP and 80 percent of emissions.

And throw into the mix smaller V20 and European economies always—by virtue of size and hence international interdependency—better multilateralists. Make it a club with rules and mutual accountability that seeks to build around trade, investment, and innovation a shared green marketplace and society.

Current COP summits are like an onion. At the core are the governments and multilateral bodies making the too-often limp decisions. The next layer is the “trade fair” of businesses, entrepreneurs and technologists in the expo. Then there are the civil society organizations agitating for greater ambition and radicalism beyond the security cordon.

The fundamental problem is that those layers interact much less than they should:

- the governments and the targets they agree typically have too few links with the “trade fair” and civil society elements needed to make it happen,

- the businesses and technologists in the trade fair often have brilliant ideas but may lack the access to the levers—political, economic, and social—required to make these reality, although my suspicion is that the businesses—for all the jibes about “greenwashing”—may have contributed more in reality to slowing climate change than the declarations stemming from the inner governmental onion,

- and the civil society voices, and more widely the citizens they represent, are too often left to protest outside the conference venue—and depending on the host they are sometimes not even allowed to do that.

Bluntly put, we cannot save the planet unless we overcome those barriers. We need to steam the onion to the point where they break down and meld together.

Start with the core of the COP onion and its outermost layers. What can we do to shorten or eradicate the distance between those at the podium and those beyond the barricades?

Here I want to go back to national politics. My answer is that the activists need to seek and wield power. The protest movement has to win office. Greta Thunberg has to run for the Swedish Parliament!

Several notable figures have already taken this step. The mother of activism-in-office was surely Wangari Maathai, the founder of the Green Belt movement who was elected to the Kenyan parliament and went on to win the Nobel Peace Prize.

More recently we have seen figures like the great Latin American conservationists-turned-politicians Carlos Manuel Rodriguez and Marina Silva, Ireland’s first “nature minister,” and former campaigner Malcolm Noonan, and his Canadian counterpart Steven Guilbeault who could once be found dangling off the CN Tower in Toronto with a protest banner.

And indeed Greta Thunberg’s Austrian counterpart Lena Schilling who is running for the European Parliament in June.

Running an organization that funds democracy activism, I would add that the problem is even wider than climate. Political parties and often political leadership have been captured by old men.

A 77-year-old and an 81-year-old stumble weak-minded towards America’s day of destiny in November. The membership of Britain’s governing Conservative Party averages about 60. In West Africa elderly democratic leaders who have outstayed their welcome are falling to young army officers and leaders of social movements who are being welcomed by citizens who think their democracy had been captured by aging elites.

Democratic innovations that intensify accountability and participation in climate policy-making beyond four- or five-yearly election cycles have a crucial role to play. In recent years a number of states have experimented with citizens’ assemblies, juries invited to deliberate on thorny and morally complex collective challenges.

Ireland for example used such a body to pave the way to its referendum in 2018 legalizing abortion. Clearly there is a role for such innovative methods in navigating the distributional issues and other trade-offs involved in cutting emissions and protecting eco-systems.

That is one form of hybridity. But there are others. I can’t be the only one here who finds the “trade fair” element of the COP summits the most encouraging.

Yes, there are businesses that hold out against every climate advance and spend vast sums lobbying accordingly.

But there are also entrepreneurs, investors and technologists delivering radical breakthroughs in the direction of zero-carbon prosperity:

- Two weeks before COP28 finally broke the taboo on the need to “transition away” from fossil fuels, the first transatlantic passenger plane powered purely by sustainable aviation fuel successfully crossed the Atlantic in an illustration of the gulf between government targets and real-life progress.

- Other such developments include the cutting-edge progress in clean nuclear fusion, hydrogen-based energy storage, as well as the use of satellite data and AI to track and anticipate threats to biodiversity.

It also makes sense to look at the deeper economic tectonic plates. Capitalism is changing, whether or not it ideally wants to do so:

- fossil fuel mineral reserves like oil and gas matter less, and battery-relevant mineral reserves like lithium and cadmium matter more,

- profit incentives are being transformed; with the share of emissions covered by carbon pricing and emissions trading rising from 7 percent 10 years ago to about a quarter now,

- and this is all changing faster than many want to acknowledge: not only rich countries but also middle-income ones like Indonesia and Mexico are rolling out ETS emissions trading systems.

Elsewhere economists like Mariana Mazzucato, a grantee of ours, are starting to define a new economic paradigm, with a more prominent role for state-led investment but also new fusions of between state, market, and society that I believe will ultimately supplant the old neoliberal order as that once supplanted the New Deal order in the 1970s and 1980s.

At the international level, initiatives like Bridgetown speak of a new wave of ambition when it comes to addressing the financing gap faced by low- and mid-income states.

Economics generally lies upstream of politics. And thus, the hybrid politics of the climate-crisis era is also taking shape.

The left wants transformation. The right wants conservation. Fusing the two is eminently possible but requires an overhaul of the political economy. All of that can add up to a winning electoral formula. What hurts is when one or the other exclusively claims the issue as their own.

The Swiss Alps are the perfect place to reflect on that. It was here that Jean-Jacques Rousseau roamed through the valleys and meadows as he formulated the republican politics that would go on to influence both Girondin (that is, reformist) and Jacobin (or, revolutionary) traditions of Western political thought.

No one such school has a monopoly on nature.

Conservatism too has its claims on the tradition. It is not that long ago that the Democrats as the party of the big cities and cheap food had a tin ear on the environment and the Republicans as a party of asset owners believed in land conservation.

It was Ronald Reagan who made possible the Montreal Protocol on ozone depletion in 1987. It was Margaret Thatcher who in 1988 argued that climate change was real and significant. It was Angela Merkel who led the first ever COP conference in 1994 as Helmut Kohl’s environment minister.

In that tradition, and its revival, lie the seeds of new left-right pacts on climate and nature protection.

Again: hybridity, always, offers us the broad path to progress.

Before I draw this lecture to a close, let me ruminate on where that path can take us.

Example Number 1. It is 2030. We are in the Brazilian Amazon, the world’s largest reserve of carbon and biodiversity which is now growing back. Local indigenous communities are thriving by cultivating crops like açaí that support this rich eco-system rather than depleting it. Their political and societal power grows as they do so.

Example Number 2. It is 2035. The Inflation Reduction Act in the U.S. proved to be just the start, triggering a virtuous cycle of investment and cleaner energy across the global economy. It has not tipped into trade protectionism by another name, but led to a like-minded community of states that have transformed their economies and are now trade, investment and innovation partners with higher GDP growth rates than the angry diminishing group of dirtier economies that have stayed out.

Example Number 3. It is 2040. As the global community strives towards net zero carbon emissions, raw earth minerals are the new fossil fuels. But their extraction is following different and more socially beneficial patterns. Dynamic civil society groups and ethical businesses have made the lithium, cadmium, and cobalt industries fundamentally beneficial to the societies where they take place and enabled them to move up the value chain. Battery factories are rising from the African and Latin American earth, close to their new customers.

I started this lecture with a rather more pressing prospect: that of Donald Trump and the additional four billion tons of CO2 that it is estimated his second term in office would bring.

But really that was the wrong enemy to highlight. There will always be figures like Trump. They will always need to be challenged and defeated.

The more fundamental contest is the one between mutual exclusivity (“either-or” thinking) and positive-sum action (“both, and” thinking).

I have enjoyed a long and diverse career spanning the UN and Bretton Woods systems, and the worlds of diplomacy, private enterprise, and philanthropy. So I say to you all this evening: what matters above all else is an institution’s and an individual’s capacity for heterodoxy.

Old thinking, old solutions and old boxes don’t work any more. Intellectual curiosity and ambition, a quest for partnership and a deep empathy are the elements of a new leadership that can save us from ourselves.

Such is the spirit that I hope you will all take into the rest of this conference. So: as you discuss and interact here, high up in the mountains, I urge you to keep in mind the heterodox new coalitions and connections—especially the unexpected ones—that you can bring with you when you descend from here back to the lowlands, your jobs, your institutions, and your campaigns.

Thank you.

Source: https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/newsroom/climate-action-democracy-and-the-case-for-hybridity